Out on the sunny patio at Wahpepah’s Kitchen, scorching plates of bison and deer make their method down a desk stuffed with Native American educators from throughout the nation. The sport meat joins different indigenous dishes on the kitchen’s menu, akin to leafy salads topped with striped pink corn and blue corn mush sweetened with berries and maple.

Chef Crystal Wahpepah, the proprietor of Wahpepah’s Kitchen and a member of the Kickapoo tribe, is proud to see the gathering. Meals is medication within the Native American custom, and her Oakland restaurant is all about bringing collectively Indigenous producers and substances – sustainable meats, contemporary berries, heirloom corn and herbs – to assist individuals heal.

“Being a Native American chef is greater than being a chef. It’s deeper than that,” says Wahpepah. “It’s about the way you connect with the neighborhood and well being. It’s about how we impression individuals and what we put in our meals.”

Within the seven months since she opened Wahpepah’s Kitchen, certainly one of solely a handful of Indigenous eating places within the nation, Wahpepah has develop into the toast of the culinary world. She’s talking at nationwide conferences, making ready for a Food Sovereignty Symposium and Festival in Michigan, and is a finalist for the 2022 Rising Chef award from the James Beard Basis.

However for all the excitement, Wahpepah’s in a single day success has been a lifetime within the making. Wahpepah, 50, grew up in Oakland’s shut knit Native American neighborhood. She’s registered with the Kickapoo tribe of Oklahoma, like her mom and grandfather. When her mother and father break up, her father, who was Black, went again to Louisiana.

She says it was laborious being the one mixed-race child within the household, the one one and not using a father in her life. However meals traditions anchored her to her household and Native American heritage. “I ended up embracing it,” she says.

Wahpepah, a graduate of San Francisco’s La Cocina meals incubator program, launched a catering enterprise 12 years in the past specialising in Native American meals akin to salmon, acorns, berries, and her grandmother’s Kickapoo bison chili. Through the pandemic, when her rented catering kitchen closed, fellow Bay Space chef Reem Assil invited Wahpepah to take over her former restaurant house just below the Fruitvale BART station.

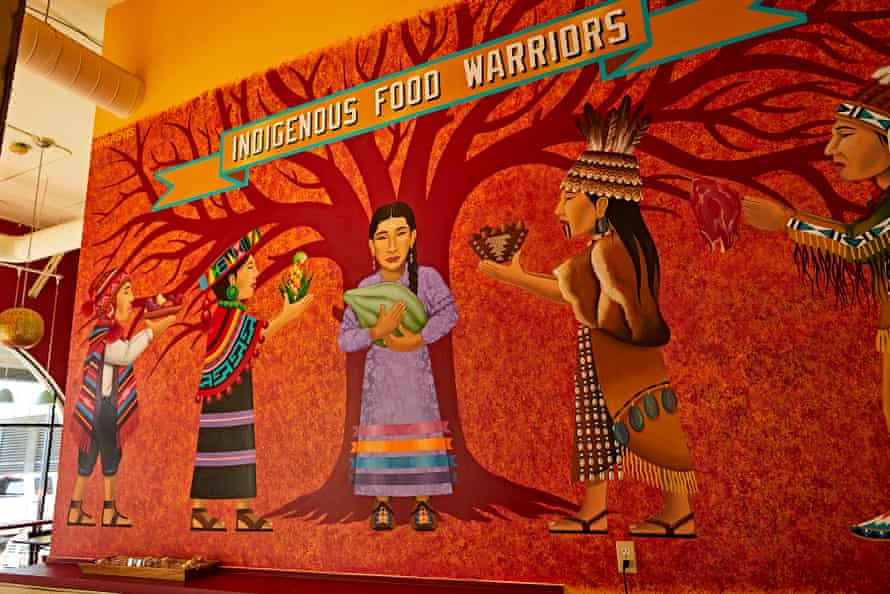

At the moment, Wahpepah’s Kitchen is a bustling hub stuffed with shiny colours and art work that tells the story of the meals they serve. A mural by the artist Votan Henriquezan depicts Indigenous meals warriors from throughout the Americas, whereas columns painted by Diné artist Tony Abeyta are adorned with golden corn – Navajo symbols of fertility and sustenance – set towards turquoise and cobalt blue clouds.

Working alongside her three daughters, Rosario, Rikki and Kala Hopper, who’re registered Massive Valley Pomo, her sous chef Josh Hoyt (Ojibwe) and Ecuadorian head chef Diego Cruz, Wahpepah’s mission is to introduce individuals to actual Indigenous delicacies whereas ensuring her household traditions endure. Take the elderberries and blackberries she likes to cook dinner with, as an example.

“I discover berries probably the most lovely factor. It’s recollections of me rising up and choosing blackberries with my grandfather,” she says. “These are the most effective instances and really one of many therapeutic instances for me. I imagine life is a circle in the way it all comes again; and if it did it for me it might probably do it for any person else.”

The Guardian sat down with Wahpepah to debate how her upbringing and heritage formed her delicacies, her ardour for meals sovereignty, and therapeutic her neighborhood via meals. The next interview has been edited for size and readability.

Crystal Wahpepah: ‘Everybody could make a distinction in our meals system’

Your meals appears like what you’d be consuming in case you had a backyard and had been in a position to forage for seasonal meals. How would you describe your cooking philosophy and strategy to recipes?

That’s precisely what we prefer to symbolize once you eat [our food]. If we take a look at how the universe works, we’re speculated to eat in a pure method in line with the season. I additionally imagine that our meals shouldn’t journey that far. If you style our meals, you style the cleanness and that it doesn’t journey. That’s my philosophy and I’m fairly certain I’m proper.

A few of our recipes, just like the Kickapoo chili, are issues that my tribe all the time makes. I additionally collect recipes from going to the library and studying Native American tales, and getting recipes from them.

It’s been ignored how lovely Native meals are and the place they arrive from. Our background comes from loads of protein, so I specialize in recreation meat, akin to venison and rabbit. My grandfather was a hunter, so when my brother hunts, he is aware of to carry it to me and I understand how to chop it.

How would you describe your mission as a chef, and what do you get pleasure from most about your job?

Our meals system is absolutely fairly unhealthy. It impacts who we’re, our vitality, the way you assume. It has quite a bit to do with despair. My mission is to have consciousness of our meals, and on the identical time make it seen to our neighborhood, utilizing indigenous data and experience to remodel the meals system. And in addition to domesticate and maintain connections to Indigenous farmers.

Essentially the most lovely factor about being a Native American chef is the neighborhood and who you get to work with … In my early days as a caterer, generally I solely bought one catering job a month. I went to loads of meals sovereignty summits and catered for lots of Native American organisations. These are the those that made Wahpepah’s Kitchen.

I wouldn’t do what I do with out my neighborhood, right here in Oakland but additionally everywhere in the nation. And being supportive and really being with Native-led individuals, and making a distinction in each baby and each elders’ life. Everybody could make a distinction in our meals system.

You utilize substances like amaranth, purple corn and Oklahoma pink hominy. The place do you discover them?

I’ve been very lucky to work with Native American meals producers. We now have smoked cedar salt accomplished for us by Sakari Farms in Oregon. The maple sugar comes from Michigan. Blue corn is from the Ute Nation in Colorado. The chocolate is from Belize. Wild peppermint from South Dakota, smoked salmon from the Lummi Nation in Seattle. A member of the Mono Nation in Fresno mills acorn flour and delivers it each two weeks. When any person involves see me from one other state, they create corn or wild rice. Deep Drugs Circle [a non-profit farm and Indigenous food collective] rising our greens.

All the pieces you see on the menu is from a Native American or Indigenous producer. Anybody who comes into my life and may supply some positivity … I do know that can switch to us and the individuals who eat our meals.

How have you ever designed your menu for therapeutic?

We come from a gluten-free food regimen. When individuals ask what’s gluten free [on the menu], I say all the things, aside from the blue corn bread. If you wish to indulge, indulge proper, and the blue corn has loads of good iron. And I like to supply loads of teas, completely different berry teas and mint teas. You’ve got wild mint, peppermint and yerba buena. Teas are therapeutic, they’re comforting.

Who taught you to cook dinner, and what are your earliest meals recollections?

My grandma Cecilia. My grandparents come from Oklahoma, and I used to shuttle there from Oakland throughout the summer season. I come from a household that cooks, and was all the time fascinated being within the kitchen with my grandmother and my aunt. I’d all the time ask my grandmother, “The place did you study this?”, and she or he was all the time telling me.

One of many first issues I made was dried corn. My aunt had a farm, pigs and the entire shebang. I used to be seven, and we’d get the corn throughout harvest, lower the corn, and put it on window screens. That’s how you’ll dry it in Oklahoma, as a result of it’s so scorching, and it might dry for 3 or 4 days, after which we might have it for soups. That was one of many first issues I ever made and and one of many issues I just about all the time copy from there.

Rising up within the Midwest, we did a unit on native Native American nations, nevertheless it in all probability was by no means correct. Do individuals have loads of misconceptions about Native American meals?

We haven’t talked about fry bread – lots of people assume that’s what [all Native Americans] made. It’s not true. And I all the time knew that, simply due to the completely different meals we had. [Fry bread] is extra like pow wow meals. It was one thing that was given to Native Americans on the reservation once they first moved onto them, in all probability within the 1800s. To this present day we eat it once I return to Oklahoma, however I eat it as a celebration, not as an on a regular basis meal.

There’s loads of dialogue at the moment about meals sovereignty with individuals of shade, particularly African People, however this was a problem first for Native People. What did being taken out of your land and conventional methods of consuming do to individuals’s well being?

It was just about [devastating] healthwise. Are you able to think about being eliminated out of your homeland? I can solely go from my very own expertise, however my household has been affected with diabetes and misplaced their limbs, coronary heart illness, most cancers and issues like that.

Me and my sister had been a yr aside. And he or she died from most cancers, forsaking seven youngsters. It makes you assume, if we simply ate higher, might we now have accomplished extra to keep away from this? It makes me need to work more durable.